As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases

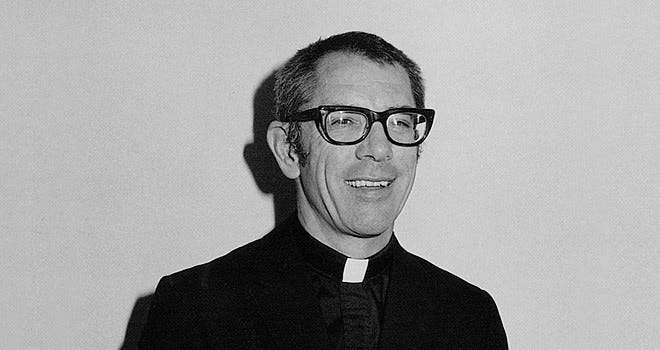

Schall, James V., S.J. Another Sort of Learning. Ignatius Press, 1988.

More a manual on how to become the lifelong learner that many educational institutions claim they want their students to become than a critical work on the great books themselves, James Schall’s minor classic Another Sort of Learning is a series of essays that prove a stirring if whimsical apologia for the intellectual life. Sage and puckish in turns, Schall is an amiable guide, leading the reader to think first about why one should set out on an intellectual journey seeking the highest things, an education that is sadly often neglected in the pursuit of one’s professional training. He then explores what that education should consist of and what value is derived from it, as witnessed by others who have gone before and left signposts to follow.

The book begins in much the same way as we begin our intellectual life, that is, in the realm of students and teachers. In these initial chapters, Schall walks with the reader, pondering not only the need to search out and find good teachers (Why Read?), but also our obligations as students, (What a student owes his teacher) and as teachers (Grades) before passing on to what it is that we ought to teach.

What follows is a series of essays on great thinkers of the past, including Plato, Aristotle, Aquinas, Shakespeare, and Chesterton. But these figures remain very much in the background. In the foreground, we have anecdotes of a life engaging with students and other academics, and informal references to scholars who have engaged with great books.

Read More: Education at the Crossroads

As such, these essays are neither introductions to the thought of these giants, nor digests, but investigations of particular aspects of their thought, and ruminations on the questions they explore. That is, we are reading Schall on McInerny on Aquinas, and only small snippets even of that. But again, this is not as troublesome as it might at first seem, as we get to see Schall engaging with a hierarchy of scholarly work, energized by the thought of the original author, carried through the conduits of these scholarly essays, an informal engagement that allows for digressions that participate in rather than distract from the point of the book: Schall makes it very clear—we are to smell the roses. Reading how and why others smelled those roses before us gives the reader models of what the intellectual life looks like, and the simple pleasure of young and old minds grappling with life in pleasant conversation, both in and out of the classroom, is one of the primary joys.

The familiarity that Schall exhibits with these thinkers is both offhand and disarming, inviting the reader to feel at home in their company. The essays are scattered with bon mots that more than repay the reader’s engagement. It is as if an expert on say Greek History has invited you on a personal tour of the ruins around Athens, and not only gives you a taste of the “touristy” general information, but invites you to dine between ventures with some active archaeologists. The insights of these encounters are surprising and at times quite profound, but also unpredictable and follow the logic of a fascinating conversation rather than a structured thesis.

Schall is also aware that he is not the show here; the works themselves which he refers to need no introduction, and he is confident that the reader who would have picked up his book would also know where to look for a list of the canon. More challenging to find are works that guide an intelligent but unschooled reader’s thinking on the questions that arise from great books. Here is where Schall’s book gives abundantly. At the end of every chapter is a small list of auxiliary works—works that act as intermediaries and ambassadors between the reader and the canon. Because the book refers to many of these writers and works within the chapters, the reader is encouraged to swing by for another go once they have done some of the suggested reading. These multiple passes become more and more enriched, the more readers explore these suggestions.

If we are to recover a sense of education as more than a set of boxes we check on the way to living lives of efficient utility, James Schall’s book will be a useful first step.

Dan Janeiro is a headmaster of a classical school steeped in the Great Books, an award-winning teacher and founder of The Banquet, a substack about the Great Books for curious parents and busy educators.